What's New

25 March, 2020

Collector clocks up the time of his life

With 90 clocks in his collection, Dennis Dowie never has to look far to know the time. The retired architect tells Helen Vause about his passion for the inner workings of timepieces from days gone by.

When you knock on the door at Dennis Dowie’s place at Stanley Point, he’ll probably know if you’re bang on time, a few minutes late or just ahead of the appointed hour.

But it’s not your timekeeping he’s that exacting about. Rather, it’s keeping a close eye on the intricate movements of his large collection of clocks and other timepieces that Dowie is really interested in.

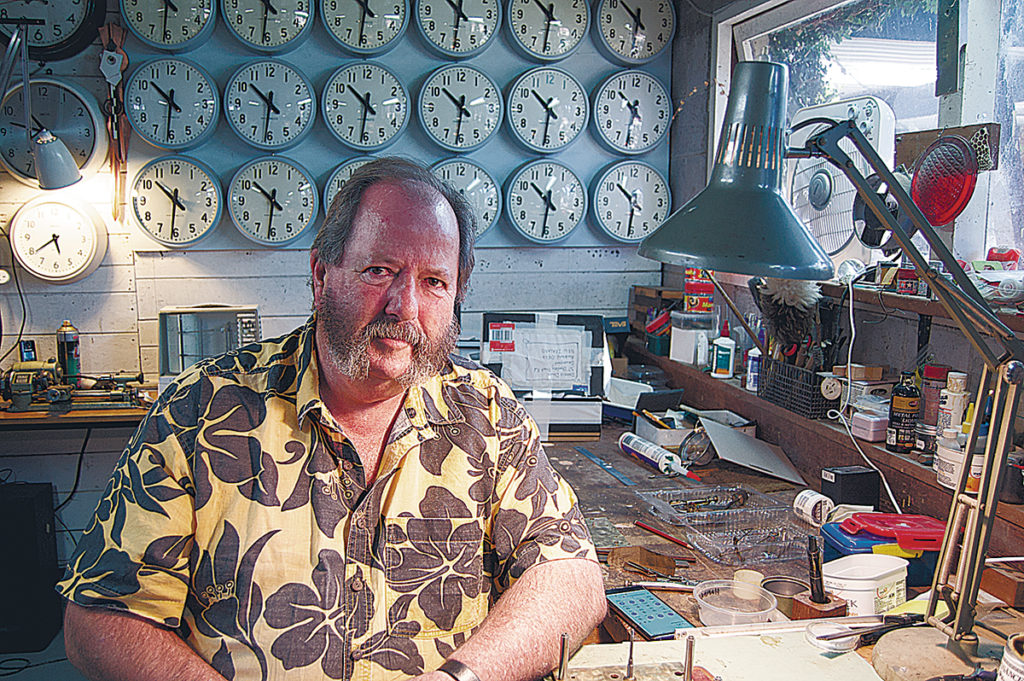

The Flagstaff was initially a little distracted by the setting and sounds, before settling into conversation with Dowie in his garden workshop. It’s the ‘engine room’ that keeps his collection ticking, putting back into working order those intruments that might otherwise have marked their last minute.

A whole bank of identical white-faced ‘slave clocks’ overlook in perfect time as he tinkers – in case he should be thinking of knocking off. Mostly from government offices around the country, they all tick in unison from an electric signal sent from their ‘master’.

But much of his 90-strong collection sits with artworks in his beautifully preserved, architecturally designed, mid-century house. It’s almost gallery-like. The eye doesn’t have to travel far before coming to rest on another piece, large or small, no longer in the original casing of its era; instead with workings fully visible in perspex display cases made by Dowie, “so you can see the interesting bits.”

Dowie is a retired architect, and crafting pleasing environments has been his working life. He reflects that it all started back in his mid-teens when his father gave him a pocket watch.

“That was pretty uncool in the 60s, when all the other guys were getting wrist watches. So I decided to take it apart, see how it worked.”

But other than the purchase of a grandfather clock in the 80s, he was a collector-in-waiting, eagerly anticipating retirement when he’d be able to pursue his passion for timepieces.

When time became his own, he wasted none of it, setting to work in his garden workshop where he’s happily spent hours and days in recent years.

Dowie’s pride and joy are not just pretty old clocks. In fact, they are mostly industrial clocks, time recorders used to keep tabs on our everyday lives, mostly in workplaces. And then there are the pigeon clocks – a key element in the world of pigeon fanciers – the workings of which captivate Dowie.

“I love the beautiful machines. I love the arithmetic and the physics of it and the precision. And I guess that is a link back to my professional life. In their beginning, clocks and time-keeping was the rocket science of the day.

“I love the science of it all and the challenge of getting things back into perfect working order. Everything in my collection is working.”

Dowie adds that his collection is probably one of the biggest in the country.

These days, an enthusiast doesn’t have to travel the world to fossick in barns and shops. The internet has made even obscure things much easier to find. Dowie spends time browsing online, and has alerts on sites such as Ebay and Trade Me that bring listings to his attention.

There’s not too much auction-room excitement and banter. His fellow collectors, says Dowie, could be anywhere, buying and often blogging about their shared interest. Some online chit-chat does occur, but the search and research mostly takes place without anyone leaving home.

“It’s hard to see how much interest is out there. But I notice when I’m bidding on something, or missing out on buying something, I like the look of on the other side of the world. It’s usually the same handful of blokes in there bidding too.”

Luckily for Dowie, his UK-based adult offspring are willing to pick up, pack and despatch some of his purchases back home to dad in Devonport.

The largest pieces in his collection are turret clocks that once stood in public places in the UK, to be read at a glance in the local vicinity. “Field workers would have been looking up at them from far off to keep track of the day.”

Pendulum clocks are another interest. Many are known as ‘one-second pendulums’ – based on the second it takes the pendulum to swing. But London’s famous Big Ben, says Dowie, has a two-second pendulum with a bigger, longer swing needed to drive the massive 10-foot arms around the clock face.

“I love the beautiful machines. I love the arithmetic and the physics of it and the precision.”

He points out a small British clock in his living room, with a bell carrying the illegible initials of the same crafsman who made the bell that still chimes from Big Ben.

And then there are the punch clocks or time recorders that were used to gauge workers’, watchmen’s, supervisors’ and others’ start and end times.

Dowie’s collection of maybe a dozen little pigeon clocks come with their own stories.

Although people have been racing pigeons through history, it became apparent in the last century that the practice of just telling of your bird’s fast arrival home was no longer reliable. With big money to be made, pigeon fanciers had to have fraudproof clocks.

Each bird carried a ring on its leg that on its arrival would be put into the pigeon clock in such a way as to store proof of the exact time.

Clubs gave some leeway in their rules about how often the clocks could be touched or opened, to compensate for jiggles on the homeward tram.

But more than a few fiddles were recorded, leading to disqualification from the race. Recently, a search for the right carbon paper to feed the record-keeping feature of one clock, sent Dowie in search to a pigeon-racing club. Sure enough, someone was able to supply the old-style inked paper he was after to complete the restoration to full working order.

One of the most irksome modern conventions for this collector and restorer is daylight savings.

“It’s a total pain in the neck,” says Dowie, just days from the next occurrence. “It takes me about two days to get them all changed over again,” he laments, adding that all year round most of them need to be wound with their own individual keys every eight days.

And the task isn’t getter any easier. “Some are stiff and hard to turn. I might need to hire a lad to wind them one day.” To those of a certain age, the clocks are a splendid, gleaming sight, with a comforting sound familiar not so many years ago.

New additions are delivered to Dowie by courier in a very sorry, silent state, however. They’ll be wrapped in newspaper and covered in dust and grime.

But then Dowie gets his skilled hands on them. “ I get them going, eventually. I work at each one quite intently.

It takes about a month, but I have plenty of time. It can take however long I like,” he grins.

This article originally appeared in the 27 March 2020 edition of the Devonport Flagstaff.