What's New

18 October, 2019

Devonport a world away from Russian labour camps.

On her 70th birthday, Aniela Bechta-Crook marked the day with a parachute jump over Lake Taupo. It was a bold celebratory gesture, but there was more to it than that. Somewhere on the way down she remembers giving the fingers to Stalin. “That was just my way to say:‘Hey Stalin, look at me. I survived.’” A decade later, on her 80th birthday Crook is putting the finishing touches to a manuscript about a different era in her life, on the other side of the world. This was a story about times and places and things from long ago, and even after half a century of life in the safety of Devonport, New Zealand, Crook was driven to capture it in print for whoever might like to know.

She was born in Poland just before her country was carved up by Stalin and Hitler, and in time to be one of the tiniest of the terrified millions of Polish people brutally rounded up in mass deportations into the depths of Russia. She was not quite four on the freezing night of 10 February 1940, when she and relativies were packed into cattle wagons for a month-long journey they would never forget. “My family of 16 were among the two million Poles deported by Stalin to Siberian labour camps, Gulags and mines between February 1939 and June 1941.” What followed for the family were terrible years of hunger, fear, sickness, uncertainty and losses, including the death of her father and baby brother. Because she was so young, when the knock came at the door on the night that changed their lives, Crook could never properly piece together the story of what had happened to her country, the people of her town, Borszczow, their friends, and their families.

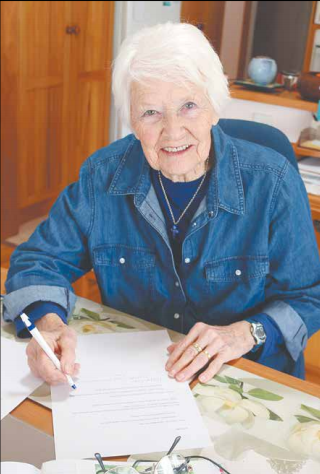

Over time, this became increasingly important to her. “Even though I have lived here for many year, and I’ve been very much part of the local community, I’d always felt I could never quite make sense of it all when it came to memories of my own story. People would only have to hear my accent, and ask where I’m from, and those feelings about that other time of my life would be there.” Crook and her husband George raised two sons in Devonport and theyowned and operated a small local kindergarten in the 1980s and 1990s. It wasn’t until retirement that she had the time and resources to begin researching and writing her own history. Her memoir With the stroke of a Pen tells the story of a family torn apart by war and runs to just under 100 pages of historic details and fascinating family recollections. When Crook talks to The Flagstaff about her early life and the more recent journey of putting it all into a manuscript, she says she has no plans to publish the stories of these Polish refugees. “But I felt compelled to record it. If only for my children and their children to read and to know. Or for anyone else who might be interested.”

Although her own partially formed memories were not sufficient to bring the early years of her history to life, she was able to capture vivid stories from her mother before she died, tracing back to that night in her village. Crook’s mother recalled the ordeal in the ‘coffin on wheels’ of rats, bedbugs, lice, gruel and the thousands who perished on the way to being dumped in Siberia. More than 70 of them were packed into each wagon. Her family of three generations, from a 60-year-old down to the young Aniela, were arguably luckier than others, because in the early part of their journey they’d not been separated. And the family was fortunate to be fortified by a mother’s moment of foreboding: the night before they were deported she’d killed, cooked and quartered their only pig, cutting it into little portions for easier concealment. It was still simmering as the family rushed to gather together a little bundle of warm clothes and food before they were pushed out that night. ‘Suddenly I remembered that I had hidden a half-full sack of potatoes under the bed, so I wrapped up some pork meat in a tablecloth and stuffed it in with the potatoes. Thank God I also gathered one of the feather duvets,” recalled her mother.

Once at the labour camps, everyone older than 14 worked from dawn until dark. They slept on floors during the freezing winter. Food was scarce, medical help non-existent. Unsurprisingly many didn’t survive. The children never questioned why they were left alone when their parents worked, why they lived as they did and had to dig with their hands in frozen soil for a stray potato. “Some of us were too young to realise much of what was happening, and in a way it would have been a bit of an adventure. It was an existence of the most basic kind – a struggle to satisfy the basic needs for food, shelter, love and intimacy. But our first Christmas in the camp was memorable because my mother found she was pregnant with my baby brother.” From that labour camp the family was moved on to another in Uzbekistan, which was where she lost her father after he fell ill and then disappeared. She lost her baby brother just a year later after crossing the Caspian Sea to freedom in 1942.

Crook traces the story of how she traversed several countries with her mother and older brother through refugee camps in Iran, India, Africa and then to England. In hope of better things, they moved to Argentina in 1951 to join family, but their reality soon became factory work rather than a better education. “After 11 years of clawing our way out of poverty, I was able to emigrate to the United States and later I sponsored my mother and brother to join me in New York.” She met her husband George in the US and was soon to join him in New Zealand in 1968. Half a lifetime later, she’s spent 15 years of research and travelling writing the numerous drafts of her story with “many thanks to my husband’s infinite patience.” The foreword has a loving note from her granddaughter.

The last pages include photos of young uncles. An archival document from Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs confirms her family as citizens who were deported from Poland to exile ‘on conviction for an administrative offence.’ The painful retracing of steps and search for information has connected Crook with many others who, like her, wanted to know about those times and lives, and to the many organisations that have formed to help them uncover more of their history. Her search took her to Uzbekistan in 2008; on to Turkmenistan and then to the Polish cemetery in Tehran, where her brother is buried with more than 2,000 other children. In 2010, she returned to Ukraine and the town of Borszczow where she was born. Crook says the cottage her father built still stands and is now occupied by a very welcoming family. In her home town, she saw one of the original cattle wagons used for the deportations. It is now a memorial. On the same trip she uncovered documents to firm up her story. She visited the birthplace of both her parents in Tryncza village in Poland and met with cousins.

Another research trip took her to the UK, seeking information from the archives of the Ministry of Defence. While there, she interviewed an ageing uncle in Coventry, who gave her all his war medals, just months before he died. Three years later, her complex web of research and connections led her to Melbourne to meet a woman who remembered her from time together in the labour camps. Writing many thousands of words has helped bring some peace for Crook, but she says there’s always a lingering feeling of “where do I belong?”. “Although my own odyssey had a happy ending in a very welcoming country, I cannot help but feel great sadness for those who are constantly risking their lives to find sanctuary. It is so very important that we give refugees the support they need to integrate into new lives.”

This article originally appeared in the October 18 edition of the Devonport Flagstaff. Download PDF.