What's New

22 May, 2018

Crown’s legal eagle stays relaxed over verdicts

Queen’s Counsel Kieran Raftery was back before the Privy Council this week, in the latest chapter of an esteemed legal career. The Crown Prosecutor, who has had a role in some of New Zealand’s most high-profile trials, talks to Geoff Chapple.

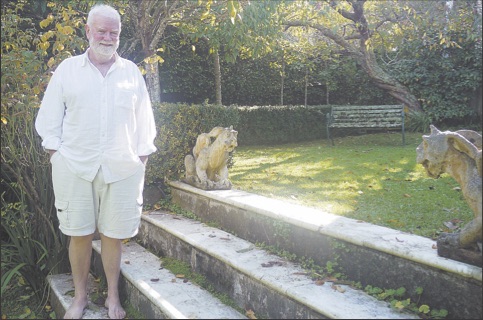

When the Flagstaff calls on Kieran Raftery, he’s padding around his Kerr St house in shorts and bare feet, preparing to depart Devonport for the oak-panelled rooms of Britain’s most august legal body, the Privy Council. Has he packed his wig, his wing collar, his bar jacket, his gown?

“On this occasion we’ve asked to dispense with those,” says Raftery, “and the Privy Council has said ‘okay’. That saves having to bring all the clobber over for just two days. It’ll be just a suit, standard business or lawyer attire.”

It’ll be his sixth appearance before Britain’s highest appeal court. Raftery has previously donned wig and gown for the David Bain and Scott Watson appeals, two of the last New Zealand cases referred to the Privy Council before it was supplanted by our own Supreme Court.

However, British Overseas Territory the Pitcairn Islands can still lodge appeals. During the disturbing sequence of under-age sex and rape trials that roiled Pitcairn Island in 2003-2007, the defendants raged against any British right to prosecute what had become accepted – by Pitcairn’s men at least – as male sexual rights. The islanders came close to besieging the Privy Council, and Raftery, as a Pitcairn public prosecutor, became a regular actor there.

The defendants claimed Pitcairn wasn’t a British ‘possession’. Even if it was, British law had never been promulgated there. Raftery argued back, and helped prime the Judicial Committee’s President Lord Hoffmann to – according to witnesses – literally laugh the islanders’ case out of court.

But no reason not to try again. In an entirely separate case, the then-mayor of Pitcairn, Michael Warren, was charged in 2010 with possessing sexually explicit films and photographs of children, and with internet-chatroom indecencies. Raftery prosecuted Warren in a trial that bounced between Auckland and Pitcairn.

The ex-mayor was convicted, sentenced, then served time on the island, but has kept fighting against any British right to prosecute. This time around, the constitutional issue is more complex. In 2010, following the earlier scandals and testing of Pitcairn’s constitutional status, Britain brought in a written constitution for the island. The new appeal has challenged that new system of governance, inching through the lower appeals process before fetching up at the Privy Council. It was due to be heard this week.

Raftery leans on a second-storey veranda rail as he recounts the Pitcairn story. Mt Victoria rises behind the house – good feng shui, he says – and from this front veranda, there are wide views across the harbour to the central city. As a Crown Prosecutor, it was his job to delve into unpleasant depths, to explore distressing detail, and to seek whatever legal traction he could compile there. Often the job was grim, and day by day, he says, it was the ferry ride back across the harbour from the High Court that helped him rinse it all away.

“That sea journey is so important. Leave the office, and take the boat, and it all just stays on the other side. Maybe you meet someone on the boat who’s got nothing whatever to do with my work – and they tell you about some trivial or funny event from their day. There’s a cleansing mechanism and the Devonport ferry is part of it, but not the only part. There’s a discipline you learn over time doing cases. You have to, as it were, clean the hard drive of your mind before you start Monday’s case. I don’t know how I do it, but I just do it. Needs must.”

And nature helps. In 2007, the Privy Council quashed David Bain’s five 1995 murder convictions and the retrial took place in Christchurch in 2009. Raftery was part of the prosecution team, rehearsing all the ghastly detail, and took time often to walk in Hagley Park, or follow along beside the Avon. After a three-month trial, the jury found David Bain not guilty.

“I’ve always made a point of not expressing views on the people I’ve prosecuted,” says Raftery. “It sounds almost indifferent, but – especially as I’ve done it so long now – I am entirely relaxed with whatever verdict comes in.

“In theory, as a Crown Prosecutor you never lose a case because you’ve seen justice done. If I know I’ve done a good professional job, then it becomes the jury’s job to decide the verdict. I’ve done my job. They do theirs. Sometimes I think, ‘Oh – I wouldn’t have done it that way’, but it’s not my job, so I don’t get upset.”

In a widely reproduced press picture, Raftery is holding out to the jury the rifle used to shoot the five Bain family members.

“I was trying to demonstrate where the fingerprints were that had been identified as David’s and his brother’s – none of his father’s. So you’ve got David pressing down, like that, and you’ve got his brother’s pressing up, like that. The reason I had the rifle in my hand was to show the jury, in a graphic sense, what the photographic ID was saying.

“I suspect while there was a lot of evidence quite strongly indicative of guilt, you also had a campaign in the press that went on for a long time. There’d been a lot of not quite trial by media, but trial in the media, and people have already begun to form, even subconsciously, different views.”

“If Scott Watson had a retrial now, a lot of people would change their evidence, not deliberately, but because the passage of time will erode their recollection. Memory is a fragile thing. It changes over time, particularly in these long-running cases, and that’s why the forensic analysis of the hairs on the [Scott Watson] boat were much more important than what Guy Wallace recalled about [dropping Ben Smart and Olivia Hope off at] a ketch.”

Raftery cleaves closely to scientific evidence, his own ability to parse complex analysis very much to the fore in his prosecutions. But he allows that a jury might not have the same priority.

“Because they have another set of abilities, perhaps saying quite the opposite.”

Justice is served then, but is it really?

“I was brought up on the maxim ‘Better that 10 guilty men go free than that an innocent man be convicted’. Though it’s better of course that the 10 guilty men are convicted and the innocent man is acquitted.”

Raftery practised law in London for 15 years, and during that time a young New Zealander off a Silverdale farm was doing her O.E. in England. They met at a party recalls Raftery, “and the chemistry said ‘yes’. I was living in Camden Town and Jan was living on a houseboat on the Thames. There’s a No 31 bus that went from the street I lived in, where it started its ride, and ended up on a street across the road from the houseboats in Chelsea. So, we carried on our romance across the 31 bus route.”

They married in 1982. Then with the birth of their son Aidan, and two years later daughter Emily, the confines of inner London began to grate, and they decided to give Auckland a try.

As Raftery recalls their arrival here, they’d come from seven sunless summers, staring across the road at a 1950s brick and mortar council block. Suddenly they were renting the front flat of a villa fronting Cheltenham Beach, the lapping sea, and Rangitoto. He loved it. The next thing was a job. He was used to being in court every day, and was told the only lawyers who get to court every day in New Zealand came from the Crown Solicitors’ Office. He applied there, and his new career began.

Raftery returned to Pitcairn in 2016 to wrap up the charges against Michael Warren, and noted “a huge shift in the mores of the island. The trials set them back a lot, but I felt they’d certainly benefited by that trial process, and the work done by social workers and various police officers who came there after the trials. The islanders felt they’d done a lot to put it all behind them, and were upset that this latest charge had undone it all.”

So to the last throw of the dice for the sex charges on Pitcairn: will the constitutional arguments of Raftery and his colleague, Pitcairn Attorney-General Simon Mount, convince the Privy Council? Or will Michael Warren’s abstruse procedural arguments succeed, and his convictions drop away?

Raftery, who was appointed in 2016 to the distinguished rank of Queen’s Counsel, knows too much about the thickets of the law to be trapped by those last questions: “I have long since given up telling myself,” he says, “that this is a winner or this is a loser – and then have the judge prove you wrong.”